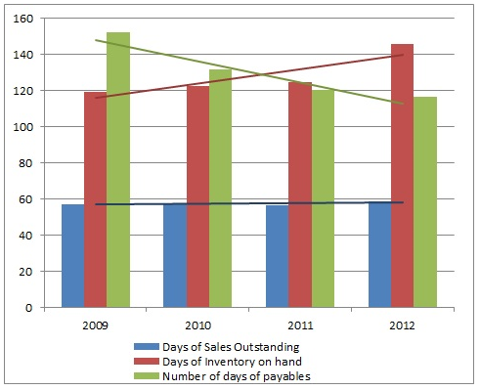

The 2007 article "Living in Dell Time" praised Dell on it's ability to push the burden of its inventory onto its supplier and, at the same time, paying it's suppliers over a month after it has already received payment from the customers. This allows Dell to boast a negative cash conversion cycle. I was interested in how companies tracked this measure. According to these articles, Johnson & Johnson and Mondelez International have their cash conversion cycle measured using "Days of Sales Outstanding", "Days of Inventory on Hand", and "Number of Days of Payables". It is easy to see how Dell beats its competitors. As you can see below, Johnson and Johnson has increased it's inventory over the last 3 years, while reducing the Days of payables, and remaining stagnant in Days of Sales Outstanding. Mondelez International is hoping to take on all three variables of the next few years. The savings from this undertaking will be "the primary driver of an approximately 60-to-90 basis-point annual improvement in base operating income margin."

It is interesting that Dell can have such success using this model, and it seems to result from the nature of it's products. Computer components have short product life cycles, so Dell could not afford to keep high inventory. When comparing Dell to Ikea, whose products can withstand a much longer shelf life and who can afford to have tons of inventory, it becomes even more clear that the supply chain is indeed designed by need. What other industries have similarly short product life cycles that could benefit from this strategy?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.