In a modern society of high product demand for a multitude

of products, one company’s inventory strategy can give them a competitive

advantage over similar companies. However, an inherent challenge associated

with inventory management is accounting for a product’s life cycle. A product’s

lifecycle will dictate how often it needs to be replenished by vendors, and how

much of it should be in stock at a given time. Errors in predicting the product

lifecycle can lead to either overstocking or under-stocking a product, both of

which will result in a net profit.

To

me, the fisheries industry presents a uniquely interesting inventory management

situation. Historically, fisheries are chronically overfished. Overfishing

results in depleted stocks that can support only a fraction of what be

harvested if stocks were maintained at higher levels. Typically this phenomenon

is modeled with an open access model

that depicts what happens when there are unregulated access and harvesting of a

common property resource. Additionally, fisheries have a considerably short

life cycle, so procurement lead times are extremely short to allow for

replenishment. By extension, I

imagine that this prevents wholesale fishing companies from performing adequate

order quantity analysis. Marginal product analysis would prove very difficult,

because suppliers cannot predict from one week to the next how many fish will

be caught. In fact, the fishery industry is one in which price per product is

constantly changing. This implies that there is significant inefficiency in the

management of fisheries inventory.

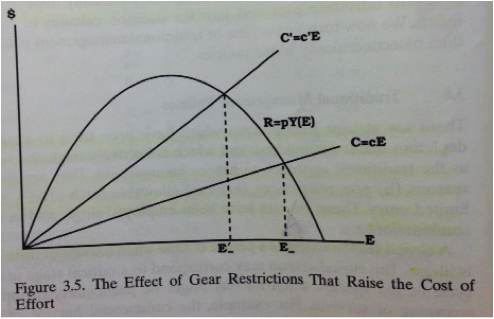

From a policy perspective, regulating

the stock of fisheries is particularly challenging. Fisheries are considered a

common property resource. Fish is not recognized as “private property” until it

is captured. There are four policies that have been used to avoid stock

depletion under open access: closed seasons, gear restrictions, total allowable

catch, and limited entry. Although helpful, none of these have succeeded in

facilitating efficiency of fishery inventories. For example, gear restrictions

are imposed deliberately to reduce the efficiency of fishers and/or to prevent

adverse impacts on the supporting ecosystem. Specifically, off the coast of New

England, the regional management council has imposed a minimum mesh size of

5.25 inches for nets to be pulled by trawlers. Gear restrictions might be

viewed as the raising of the unit cost of effort to increase fish inventory

from c to c’:

This causes the cost equation to rotate upward, establishing

a new steady state equilibrium. As such, gear restrictions reduce effort, but

do not really address the underlying problem of inventory inefficiency and a

resource being harvested to the point where is has a zero marginal value.

The inability of traditional management policies to stop the

phenomenon of over-fishing has led to a discussion of the potential to apply

“incentive-based” policies, such as Individual Transferable Quotas. This is

essentially a cap-and-trade system, applied to fisheries. At this point, I

wonder if such a system has the potential to alter the nature of fisheries

inventory management, or are the major fisheries players to set in their ways

to be open to such a change.

References:

Resource Economics,

Jon M. Conrad, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

“Managing Inventory,” Hammond, Harvard Business School.

Nice post, thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteMore details Visit our website:

Global value Chains india Policy perspectives

www.indianwesterlies.blogspot.com