The articles demonstrate how both TATA and IKEA have incorporated

modularity to gain an edge over their competitors, both in terms of efficiency

and cost. This reminds me of economic concepts on “Comparative and Absolute advantage”,

allowing stakeholders to be better off through the creation of surpluses, which

would otherwise have been lost as the opportunity costs are too high.

In short:

"A person has a

comparative advantage at producing something if he can produce it at lower cost

than anyone else. Someone who is the best at doing something is said to have an

absolute advantage. What it costs someone to produce something is the

opportunity cost—the value of what is given up. Someone may have an absolute

advantage at producing every single thing, but he has a comparative advantage

at many fewer things, and probably only one or two things."[1]

For me, this concept of trade can be applied to

manufacturing allowing to generate that additional surplus through efficient

resource utilization. The articles demonstrate how companies have made use of

modularity to benefit at various stages of their supply chain.

Fig 1: Five Steps of Supply Chain Management[2]

Furniture retailer, IKEA plans for a new product by

analyzing gaps within its product lineup and by assessing the product need for

the identified segment. The price is then determined by surveying the market

and undercutting the competitors by 30-40%.

Next IKEA designs the product in house and looks towards its

distribution centers (located in 33 countries worldwide) to provide the most

suitable design package, focusing on price and quality. This allows IKEA to

choose multiple suppliers to create a single product, allowing for lower cost,

quality and efficiency. To achieve this modularity, IKEA fosters strong

relationships with its suppliers to garner trust and promises them large volume

orders, which allow for economies of scale. This way suppliers can invest in

equipment and cost saving techniques to generate efficiency as they do not have

to worry about being idle or the risk of their investment going down as sunk

costs.

Lastly IKEA has built upon its modular manufacturing

technique to revolutionize its delivery and logistics stage. Most IKEA’s

product components only meet at the store and are flat packaged to save space.

This allows IKEA to save 83% on the volume of goods shipped and also allows

them to save space in their stores.

Incorporating modularity, allowed IKEA to enjoy 20%

increases in growth for 5 years, hence generating that surplus to propel itself

ahead of competition.

TATA has used modular design in a different setting allowing

it to gain an edge over competition. It has utilized its open distribution

innovation to tap the local parties to drive down costs and reach a wider

audience. Involving local parties allowed TATA to generate a sense of ownership

amongst the community, encouraging ideas and innovation. Being part of the

supply chain motivated third parties to reach remote areas and understand the

needs of the market.

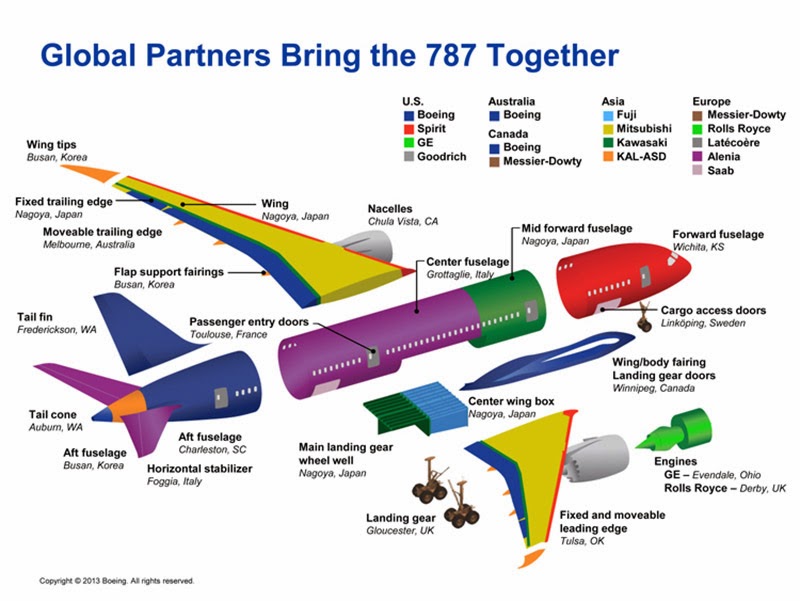

A similar approach was adopted by Boeing to manufacture its

787 aircraft. Boeing used various countries to make specialized parts for the

aircraft and brought them together to benefit from heavy manufacturing costs

and storage costs.

Fig 2: Five Steps of Supply Chain Management[3]

Hence using a modular design approach leads us to think in

terms of specialization. Saving time and maintaining quality to generate volume

helps to lower down costs and expand your target market. Focusing on producing

a specific component in large volumes, rather than the whole product allows

manufactures to invest in specialized machinery as well as save space on

factory floor. A good example is the design of the T25 and T27 cars by

automotive engineer Gordon Bay[4]

who was able to reduce the amount of capital investment through reducing the

space needed for production. His assembly design allowed for factory size to be

reduced by 80%. He was able to use lighter parts, which saved transportation

costs, reduce the emissions footprint, and a simplified assembly process

allowing him to locate production near to customers hence allowing for a

modular approach whereby assembly plants were located adjacent to points of

sale and service.

Can modular

design approach go wrong?

Having discussed the advantages of using a modular approach,

it makes me bit skeptical not to think if the same approach can wreak havoc for

companies.

While we see a successful implementation of modular design

in the manufacturing of Boeing 787 it was plagued with issues that caught media

spotlight. For instance fires that broke out in two of Japan Airline’s aircraft

at the Boston Logan airport one due to fuel leak and other due to battery

issues, and the electrical failure in the power distribution panel on a United

Airlines 787 aircraft resulting in an emergency landing.[5]

Does adopting a

modular approach at one stage strain or demand more attention to other stages

of production?

Can designing products

in modules (utilizing different suppliers for components) compromise quality?

From experience, I have observed that such an issue is not

only prevalent in manufacturing something as complex as an aircraft but as

simple as assembling a car. When Suzuki launched the Cultus hatchback in

Pakistan it was imported into the country. However, later on assembly plants

were setup in the country that would get parts of the car and put them

together, something similar to TATA distributing NANO kits to local assemblers.

Noticeably, there was a decline in product quality and the amount of complaints

arose. Issues such as lights not connected to the car’s electrical system or

emergency brake not functioning to cars missing bundled tools started to

increase. Though the whole car costing cheaper to make dented the reputation of

Suzuki to some extent.

Does it make it

trickier to align with other supply chain models?

Lastly, we have the example of the unsuccessful merger

between Daimler Benz and Chrysler[6],

both successful companies, declare huge losses due to incompatible supply chain

models. Daimler operated on an integrated model while Chrysler relied heavily

on a modular approach causing the incompatibility. In essence Chrysler made

standardized cars, offering little customization but producing high volumes,

while the Benz mantra was high cost customized hand crafted vehicles. Both

companies were unable to synchronize their supply chains to collaborate on

creating a successful vehicle. Could they have taken steps to produce a

competitive and cost effective product without disturbing their core processes?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.